Modeling a Returns Waterfall

One of the most complicated parts of your model is also one of the most important: modeling "Returns."

"Returns" is the section of your model that tells people how much money they made (😬 so don't mess it up).

It's usually the final part of your LBO model, and is a critical piece of the ongoing diligence process, as changes in company performance affect investor returns.

Let's talk through how to build it today...

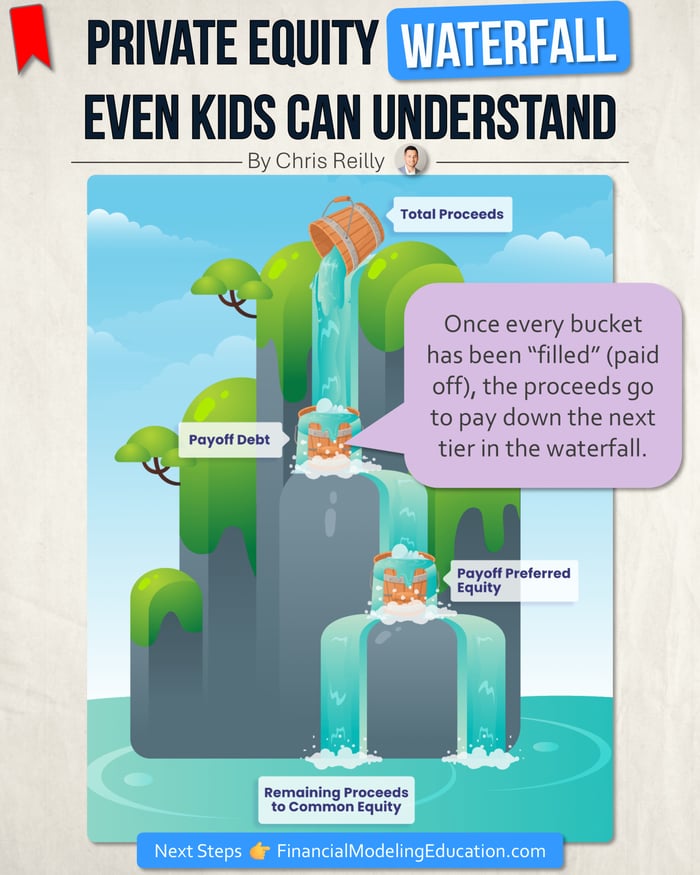

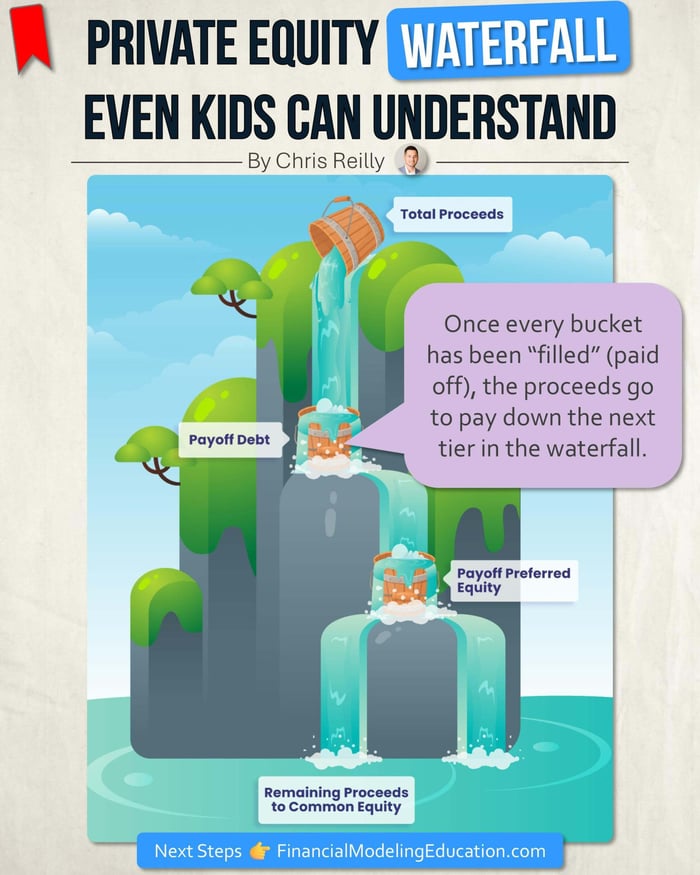

Returns Waterfall: A Simple Version

|

Let's start with the basics, and then we'll talk through a more complicated example.

Enterprise Value

When a company is sold, the Purchase Price is often called the "Enterprise Value" (or "EV").

The EV is typically calculated as a multiple of Adjusted EBITDA.

In the image above, the Enterprise Value is the Total Proceeds at the top of the waterfall.

Payoff Debt

The Total Proceeds pay things off in order of priority.

First, the Total Proceeds "flow" down the waterfall to first tier, the Debt.

The Debt needs to be paid off in full before the waterfall can "flow" to the next tier.

So in the image above, the "Debt bucket" is completely full before it overflows and continues down the rocks.

Preferred Equity

Then, the Remaining Proceeds "flow" down to the next tier, the Preferred Equity.

(this is, of course, if the cap table has Preferred Equity, but it's common to see in Private Equity deals)

Just like the "Debt bucket," the "Preferred bucket" needs to be fully paid off as well before the water can flow further.

Preferred Equity comes with a few complicated features that we'll discuss below.

Once the "Preferred bucket" is completely full, the water overflows and continues down the rocks.

Common Equity

Finally, to the extent there are proceeds leftover, the rest goes to the Common Equity holders according to their "pro rata" share.

(in other words, how much of the Common Equity they own)

This can be the biggest pool because there's no "bucket" to fill, but the risk is of course that the Common Equity comes last in the waterfall.

If you'd like to see a short video on how this works, I have one on YouTube here:

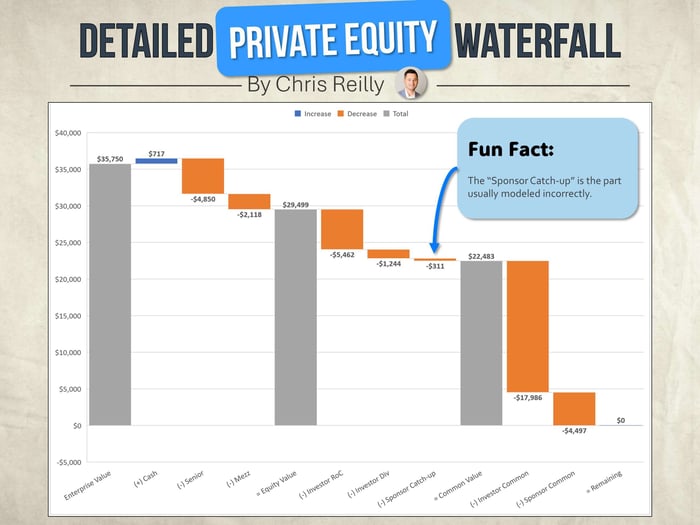

Returns Waterfall: An Advanced Version

|

Now let's step it up a notch and talk through an advanced returns waterfall, like the one you'd find in an LBO model.

From the top...

Enterprise Value or "EV"

Like we said above, this is the Purchase Price of the company for sale and gives us our Total Proceeds starting number.

Typically calculated using TTM Adjusted EBITDA multiplied by a “market multiple.”

(in this example it was $5.5m x 6.5x (not shown) = ~$35.75m EV)

Plus (+): Cash on Balance Sheet

We add the Cash to the EV because the Seller gets to keep any cash at closing.

Why? Cash reflects value the Seller has created in the past (so it's theirs to keep, not the new buyer's).

Often times, sellers will agree to leave a minimum cash amount in the business and only keep the "excess cash." This helps with working capital management after the deal closes.

Minus (-): Senior Debt

Now we start to pay down debt.

Just like the value of a house, your “equity” is what’s leftover after you pay the mortgage.

In this waterfall, the Senior Debt has “priority” so it’s paid down first.

Minus (-): Mezz

“Mezz” is short for “Mezzanine” — another type of debt.

In this waterfall, the Mezz is “junior” to the Senior Debt, so it’s paid down second.

Subtotal: Equity Value

All of our debt obligations have been paid off, so now we have “Equity Value,” or what’s available to be distributed to all equity holders.

This is the first subtotal in the waterfall, denoted by the gray bar.

Minus (-): Investor RoC

“RoC” = “Return of Capital”

Often times certain investors in the deal will hold “Preferred Equity” (like we discussed above).

All this means is these investors are paid out first before any Common proceeds (but after debt).

Minus (-): Investor Dividend

This “dividend” is associated with holding “Preferred Equity.”

Not only do these investors get their capital out first (above), they also get something called a “Preferred Dividend” on top of their investment.

This is often called the “hurdle” because it must be “cleared” before proceeds go to Common.

Minus (-): Sponsor Catch-up Provision

Now that investors have received all their capital plus a preferred dividend, it’s time for the Private Equity firm to get their share, or “catch-up” to what has already been distributed.

In an 80/20 split, the investor dividend (up to this point) equals 80% of the proceeds so far, and the “catch-up” is the other 20%.

❌The Wrong Way: Multiplying the Investor Dividend by 20%.

✅The Correct Way: Dividing the Investor Dividend by 80%, and then subtracting the Dividend.

Subtotal: Common Value

Finally, we’ve reached the Common Shareholders (the big pool at the bottom).

This is everything that is leftover after all other obligations have been paid off.

Under this deal, the remaining proceeds get split 80/20 to Investors/PE firm.

**Double-check: investors should get 80% of the gain, PE firm should get 20% of the gain (if not, something is incorrect above).

**Final Note: The “deal returns” shown here reflect the distribution from a specific transaction, whereas “investor returns” also account for management fees paid at the “fund level,” which cover operational expenses and impact the overall net returns seen by the investors (not shown in this example).

The Big Picture

Typically, the Senior Debt receives the lowest return because it has the least amount of risk in the "capital stack."

(because it's paid out first)

The Mezz has a higher interest rate (and therefore higher return) because it gets paid out in the middle.

You work your way down to Common, which can create the highest returns but also carries the most risk.

(because it's paid out last)

This is such an important section in your financial model because it assess the viability of the deal for investors, so make sure you build the "double-check" I described above (ensuring investors get 80% of the gain, and the PE firm gets 20% of the gain).

That's it for today. See you next time.

—Chris

p.s., if you enjoyed this post, then please consider checking out my Financial Modeling Courses. As featured by Wharton Online, Wall Street Prep, and LinkedIn Learning, you'll learn to build the exact models I use with Private Equity and FP&A teams around the world. 👉 Click here to learn more.