What is the Matching Principle?

In the world of financial accounting, the Matching Principle stands as a cornerstone, ensuring that companies accurately report their financial health.

tl;dr: my free email series covers Financial Modeling in detail, sign-up here.

Unlike cash accounting, which recognizes transactions when cash changes hands, the matching principle dictates that revenue is recognized when earned, and expenses are recognized when incurred.

The key thing to note here is "earned" and "incurred" do not mean received or paid in cash.

Simple example: if you do 1 hour of work, you've "earned it," but you probably won't be paid in cash until later.

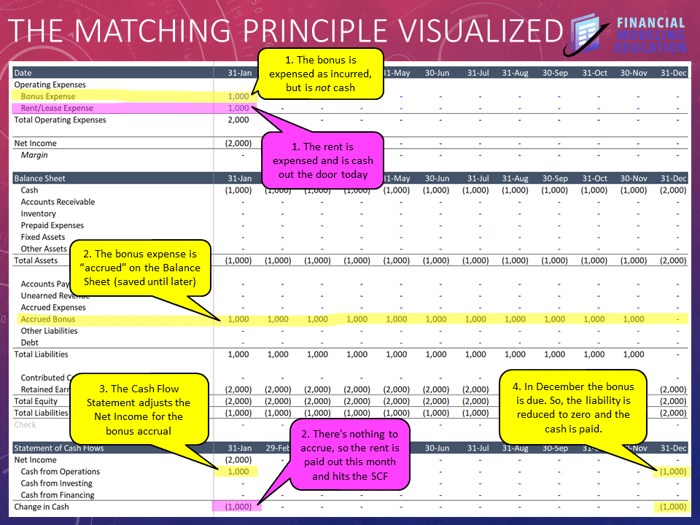

Rent (Pink Boxes)

Follow the pink boxes for the Rent Expense.

This is the easier of the two.

The business incurs a rent expense in January.

The rent expense is also paid in cash in January, so there's nothing to reflect on the Balance Sheet.

Rent Steps

1. The expense hits the P&L

2. The cash leaves the business in the same time period

(January rent is paid in January)

Bonus (Yellow Boxes)

Follow the yellow boxes for the Bonus Expense.

This one is harder because the incurred expense doesn't match the cash outflow.

The business incurs a bonus expense in January.

But, the bonus isn't paid in cash until December. So we have to reflect that accrual on the Balance Sheet.

Bonus Steps

1. Incur the expense in the appropriate period (January)

2. Accrue that same expense to our Balance Sheet in the Accrued Bonus account (in other words, "save it for later")

3. The Cash Flow Statement adjusts our Net Income to say, "yes, I see that you've incurred an expense, but for cash purposes we're adding back the $1,000 in January because it actually won't be paid out until December."

3a. This is why it's called the "indirect method," because our Cash Flow Statement is indirectly adjusting the Net Income to show us the cash.

4. In December (when the cash is actually due), the Accrued Bonus account is reduced to zero, and the cash leaves the company at the correct time.

Big Picture Impact

The company incurs $2,000 worth of expense in January, but...

It is paid out in cash as follows:

- $1,000 in January as Rent

- $1,000 in December as Bonus

Follow the bubbles in the image to see it play out.

Other Scenarios (Not Shown)

Just to round out the topic a bit more, here are a few other examples:

Manufacturing

Consider a manufacturing company that incurs costs in producing goods.

These costs (raw materials, labor, etc.) are recognized as expenses in the period the goods are sold, aligning the expense recognition with the associated revenue.

However, the cash may have gone out the door much earlier than when the goods are recognized as sold, especially as it relates to raw materials, which are often purchased in advance.

Projects or Contracts

Another scenario involves long-term projects or contracts.

Companies recognize revenue and expenses over the duration of these contracts, aligning the recognition with the progress of the project.

For a project, this might be done using the "percentage completion" method or some other milestone-based schedule, but the cash timing would often be different.

Perhaps easier to understand, take your basic SaaS contract: a 12-month contract paid upfront. Cash comes in the business today, but the Revenue is recognized over the next 12 months (matching the contract), which means the offsetting entry goes into Unearned Revenue as a liability on the Balance Sheet.

(the cash has been collected, yes, but the Revenue is yet to be delivered to the customer, and therefore isn't technically earned).

Depreciation & Amortization

Depreciation and Amortization expenses are allocated over the useful life of an asset, matching the expense recognition with the period the asset contributes to generating revenue.

A simple example I always like to use here is a truck: If I buy a truck with a seven year useful life, I will use cash today to purchase the truck, but I will expense the truck in the form of depreciation over the next seven years because it helps me generate revenue during that time period (by making deliveries).

Conclusion

The Matching Principle is more than just an accounting rule; it's a lens through which the financial health and performance of a business can be assessed more accurately.

While it may add complexity to financial modeling, it is critically important to create a truthful picture of a company's financial situation.

Found this post remotely interesting? My free email series explores the intersection of Financial Modeling, FP&A, and Private Equity to help make you a better Financial Modeler. Sign-up free here.